Mayor Jerry Brown’s call for large-scale development in downtown Oakland-known locally as “10K”-has been covered in media around the country. Many longtime Oakland observers are glad for the gleam he has brought to Oakland’s image, and environmentalists hail the Mayor’s program as an important campaign in the relentless outward march of suburban development.

To publicly commend the initiative, and to ensure that policies are in place to shape the physical and social components of downtown development, Urban Ecology released an open letter to Mayor Brown in December 1999. The letter calls for a transit-first policy for downtown, a program of development fees to build and maintain public parks, and an inclusionary zoning ordinance that would require 10% of all newly developed units to be priced affordably to residents at 80% or less of Oakland’s median household income.

Unlike Oakland, many Bay Area cities are planning the majority of their development in single-family, low-density homes on the edge of existing suburbs. The region faces a 250% rise in congestion, and 490,525 acres of agricultural land and open space are at risk of development. Transit ridership is projected to decline-leaving little hope for the region’s worsening air quality.

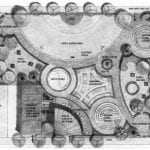

While demonstrating support, Urban Ecology has asked Brown to do more to allow public participation in crafting policies that will ultimately determine the downtown’s character. Oakland’s General Plan, while approved in 1998, sets only broad guidelines for land use and development. It contains no urban design guidelines, which would establish parameters for building height and bulk, the relationship of building facades to the street, and the look and feel of downtown streets themselves-the width of sidewalks and roads, the benches and features for public use, the prioritization of transportation modes. The General Plan also lacks strong recommendations-backed up by programs-to create public open space as downtown grows more populous.

Indeed, an assembly of neighborhood groups, affordable housing advocates, and preservationists has been brought to its feet by the expected sale of four city-owned properties to private developers. The proposals, which ranged in size from 3 to 22 stories and 90 to 234 units, faced a packed city council meeting in December 1999. Opponents complained about the height, bulk, density, and price range of the projects.

Affordable housing in particular poses a conundrum for every city and county in the Bay Area. Urban Ecology and other groups are working to build political will for affordable housing around the region, but few jurisdictions have policies that protect a portion of the housing market for the working poor or those fully dependent on subsidies. In the white-hot real estate market, even fewer are receptive to developing such programs.

Oakland, home to a proportionally larger poor population than much of the region, faces the problems of dwindling housing supply and diminishing federal subsidies with few affordable housing programs or policies. The city has taken some steps: Proceeds from the sale of the city-owned property last December will be placed in a trust fund to subsidize affordable housing units. (The expected $4.5 million can be leveraged with state and federal funds into ten times that amount, supporting 200 units of affordable housing.)

In part because of the local uproar, Urban Ecology urged Oakland’s political leaders to establish a means of public participation. The City of Oakland’s Housing Task Force was established in February 2000, and as a leading participant, Urban Ecology proposed several city-wide housing policies. The Task Force’s full package of policies — many of which establish housing policy for the first time ever in Oakland — was unanimously adopted by the City Council in July 2000.