How do people who speak five different languages talk about a common future for their neighborhood? Translation.

Not just translation from one language to another, but translation from the language of planners to that of everyday people.

This kind of translation defines Urban Ecology’s role in Oakland’s Lower San Antonio, a culturally rich but low-income community where almost half of the residents are foreign-born. For the past two years, at workshops, in small groups and one-on-one conversations, UE has reached out to residents to listen to what they want for their neighborhood. Their answers serve as the foundation for a new set of community goals for 23rd Avenue. These goals are the heart of a UE-written action plan for revitalization, due out this spring.

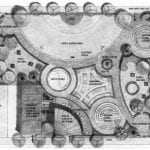

Two major themes emerged in our two-year planning process: The desire for safety – both from speeding cars and from crime – and the desire to somehow capitalize on 23rd Avenue’s unique blend of arts, learning institutions and culture. To respond to the first concern, UE has recommended a series of streetscape improvements that will make 23rd Avenue safer for walking, biking and using the bus. In addition, UE is linking local concerns to regional transportation issues – such as the need for time- and cost-effective ways for residents to access jobs in other communities. Finally, we are also strategizing with local organizations on how to create a community cultural center that can act as an anchor for 23rd Avenue, a hub for classes, after-school activities, and performances. In coming months, UE will identify properties along 23rd Avenue that might be developed into a culture center; we will also be working with local groups to secure funding for such a center, and to improve local traffic issues.

History of the Area

Oakland’s “lower” San Antonio is a flatlands neighborhood nestled next to BART tracks, railroad tracks and the I-880 freeway. The Lower San Antonio was originally a Mexican land grant. In the late 1800s it became a spot for summer homes owned by the wealthy in San Francisco and, by the turn of the last century, became a streetcar suburb.

In the heart of Lower San Antonio sits 23rd Avenue. Until the 1940s, 23rd Avenue was a lively district with two movie theaters, several banks and hotels, a Carnegie library and, at the foot of the strip, a cotton mill that provided jobs to local residents. By the late 1950s, the mill had shut down and an elevated freeway was built, effectively cutting off the community from its economic base and from the waterfront, which is less than a mile away.

Today, the heart of the community remains along 23rd Avenue, but it faces many challenges. Fast-moving traffic and vacant lots break up street activity. There are deteriorating storefronts and boarded-up buildings. Residents of the community speak more than 25 languages, and one-third of them live in poverty. These characteristics mean that residents face language barriers, cultural differences, and limited financial means – making it more challenging to advocate for improvements to their community.

Despite these challenges, there is promise on 23rd Avenue. Façade improvements are being funded by the city. A new general store recently opened. A billiards place and the local barbershop serve as local institutions and popular gathering spots for locals. There is a performance space for artists known as the Black Dot café; across the street is the city’s largest youth employment program, and, around the corner, a thriving artists’ collective. Two schools are within two blocks of 23rd Avenue and – significantly – a new arts-focused middle school is proposed for a large site at the base of 23rd Avenue, providing the potential for new foot traffic and life.

Involvement of Other Organizations

Nearly 50 community-based organizations are involved in an initiative aimed at improving the Lower San Antonio. They are structured in “working groups” that address issues such as housing, health and business revitalization along 23rd Avenue. Urban Ecology was invited to lead a community visioning process for the working group focusing on 23rd Avenue. Urban Ecology’s challenge in this process has been to balance the agendas of many different organizations and craft a community action plan that takes into account residents’ desires and what is realistic. Specifically, Urban Ecology has identified physical barriers to community well-being through an analysis of land use and transportation issues, facilitated workshops and discussions with nearly 500 residents and a dozen community organizations to develop goals for 23rd Avenue and crafted a community-led vision for 23rd Avenue. The forthcoming 23rd Avenue Community Action Plan will chronicle extensive community involvement, community goals and next steps for improving this promising area.

Much of the work in the Lower San Antonio is funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which is funding a multi-year initiative aimed at improving the lives of low-income families and children. As part of this work, Casey realized that the neighborhoods in which families live – and the quality of housing, accessibility of transportation, safety to streets – play a crucial role in residents’ health and well-being. Therefore, a significant portion of Casey’s work in the Lower San Antonio has been to craft solutions that can fix the physical environment.

For more information on the Making Connections Initiative in the Lower San Antonio, go to www.urbanstrategies.org/LSA/LSA.htm

23rd Avenue Vision Statement:

We envision a Lower San Antonio with safe streets and beautiful open spaces, with housing and transportation options that serve the community, and with a lively cultural district filled with stores, services and organizations that serve – and reflect the cultures of – Lower San Antonio’s diverse residents.