by Randy Hester

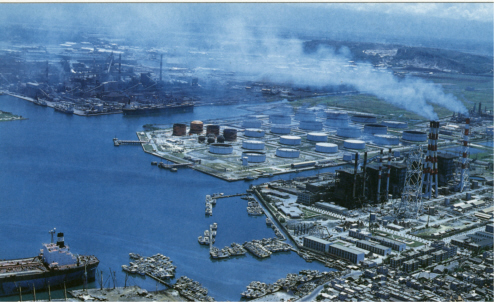

The waters of Tsengwen River and Chi Ku Lagoon along Taiwan’s southwest coast are the scene of a controversy that is increasingly familiar around the world. Taiwan’s President Lee Tung Hui and many land speculators support a 7000-acre development called the Bin-nan Industrial Complex that would fill part of Chi Ku Lagoon with an oil refinery, a steel mill and an industrial port. But environmentalists point out that the lagoon development will destroy wetland and mangrove habitat critical for the survival of the Black-faced Spoonbill, one of the rarest birds in the world. Queen’s University Biologist Vicki Fiesen predicts rapid extinction for the Spoonbill if the industry fills the lagoon and wetlands. When warned of this danger, President Lee reportedly stated that jobs are more important than any bird.

A classic case of jobs versus the environment? The Bin-nan Complex will indeed create more than 8,350 jobs in plant operation, plus thousands of semi-skilled construction jobs over the next decade. This prospect appeals to parents whose children now leave the coastal area for similar jobs in Taiwan’s larger cities.

But after construction is finished, the number of jobs created by the Bin-nan project declines dramatically. Few local people will be able to compete for high-skilled jobs in chemistry and oil refinery management. One local fisherman, Liu Shing-Tsai, commented, “We know how to fish; we don’t know how to work in a factory. We can support ourselves without this oil plant.”

Indeed, the Chi Ku Lagoon, Tsengwen Estuary and coastal waters currently provide more than 16,000 jobs in fishing and related industries. Most of these jobs will be lost when the Bin-nan industries fill the lagoon and wetlands upon which the fish and the Spoonbill depend. Fishermen’s groups led by the Chiku Fishermen’s Association have organized to oppose this threat to their livelihood, working with sympathetic legislator Su Huan-Chi, who in turn has brought in planners and designers from the National Taiwan University and the University of California, Berkeley to provide technical assistance.

Ironically, Taiwanese media have depicted these fishing communities as poor and in desperate need of industrial jobs — an image fishermen resent. Many of them have been financially successful, and are quick to point out that their work creates thousands of related jobs in processing and tourism. Another fisherman argues that the coastal communities don’t need additional jobs as much as they need clean air and water, saying “We prefer this life; it is not about prosperity.”

The fishermen are certain that the Bin-nan oil plant will make their land and water useless by poisoning oyster beds and groundwater, concerns that are supported by independent environmental assessments. The plant would also have drastic secondary hydrological impacts. It would require 121 million cubic meters of water per year (twice the capacity of existing reservoirs), and diversion dams would be required along the Kaoping River, three watersheds away. These water diversions would endanger crop production in Southern Taiwan, concentrate pollution, and flood two aboriginal villages.

Losing 16,000 jobs in order to create others requiring different skills and endangering an ecosystem that supports a stable fishing economy renders the Bin-nan complex completely unappealing. To present an alternative, the National Taiwan University and the University of California, Berkeley have worked with fishermen’s groups and dozens of expert consultants from fields as diverse as bird ecology and chemical engineering to create a different plan.

The Taiwan-Berkeley Plan creates a conservation zone to protect the habitat of the Black-faced Spoonbill. This multi-use zone would support oystering, fishing, aquaculture, recreation, and eco-tourism in addition to providing habitat protection for more than 150 species of birds. New development is directed away from the critical habitat zone and toward existing cities, towns and villages. The plan envisions a region where fishing, tourism and green industries can coexist. It would create more than 30,000 jobs with gross revenues of $525 million per year, economic development estimates nearly identical to the Bin-nan industrial plan.

It is clear that this debate does not pit jobs versus the environment. “You can have an equally robust economy and jobs to keep youth from migrating to the cities without sending the magnificent Spoonbill into extinction,” emphasizes Dr. Deborah Savage of Boston’s Tellus Institute, which evaluated the competing plans.

Certainly there are many cases in which jobs and environment are at odds, but all too often the jobs-versus-environment banner is unfurled to cover up real estate profiteering and the exploitation of both ecosystems and people. Many people in southwest Taiwan recognize that their economic stability is closely dependent on environmental stewardship. The livelihoods of fishing and oystering families, aborigines, farmers, and agricultural and even high-tech industrialists are all directly connected to the land and water. Their selfish and civic interests are served by environmentally sound actions.

The Black-faced Spoonbill and 16,000 jobs depend on the rejection of the Bin-nan plan and the implementation of the Taiwan-Berkeley alternative. The country’s Environmental Protection Administration must now approve or reject the Environmental Impact Assessment on the Bin-nan project, and is expected to act this winter.